11. The Bay

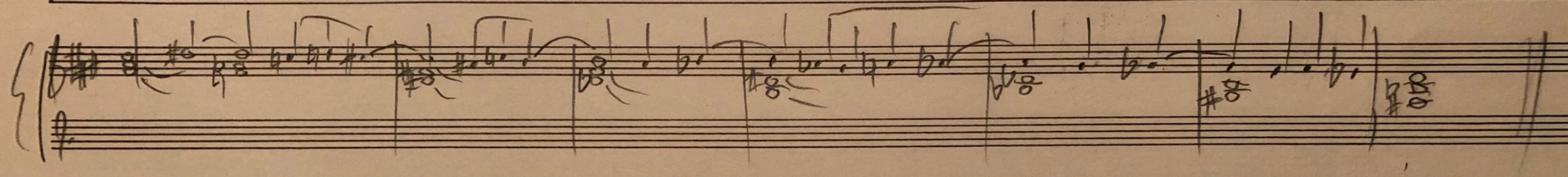

I am slowly filling in the outline of the last part. Or, actually, it is filling itself in. Not slowly either in fact, but rather quickly – I’m already on the 9th minute of runtime. After the first exchange between the Man and Woman, or Puer and Puella, which takes place against a background of silence, a hardly perceptible accompaniment of melody and harmony gradually starts to emerge. It is made of a progression drawn from the second part, when a sail appeared on the horizon. As many times before in this work, the progression is twofold: it goes up and down mirrored against D-G♯, in both cases ending with the augmented chord D-F♯-B♭:

LISTEN

The melodic themes in this progression are related to those present in the singing – both now and before, in previous parts.

References are a big topic in music. To me, it is the essence of the form. Being able to recognise something that has already been there, either changed or unchanged; to spot the difference and similarity; to grasp the reference through a sense of intellectual and emotional comprehension – all these are components of experiencing the musical form that European culture has shaped for years, quite extraordinarily, compared to the rest of the world. It has been happening in a variety of ways: some more prolific and conducive to continuation, to the extent of sometimes turning into entire movements, and others of a more episodic nature. These days, it seems the latter are more frequent, but who knows, perhaps appearances are deceptive. In any case, striking a balance between what’s brand new and recognisable, which is a basis of decisions to alternately put forward what’s expected and what’s surprising – this is what I consider the essence of music. Not always and not of all types, but certainly of the type that appeals to me the most.

I think, nonetheless, that one can't or even shouldn’t strive to strike the perfectly calculated balance, or to follow a strict plan. In this case, strategies wouldn’t be of much help. I can see a profound analogy between music and humour. Perhaps not the only example thereof, but certainly a handy one, is a joke (understood as a short story with a funny punch line). A good joke, as we all know, follows a very strict structure, yet its comicality reaches far beyond its proper form. The very same joke can either crack you up or be awkwardly, painfully unamusing, depending on who tells it, when they tell it and how they do it. For a joke to work, its precise structure must play out in a particular, unrepeatable situation, as part of a spontaneous game entailing a variety of nuances. The game is within our awareness yet beyond our control. It demands that the teller fully understand what is amusing and why, but also, at the same time, be open to chaos. That is why children are not the best joke-tellers, as they don’t yet understand how it works. The same goes for adults who can only grasp what is explicable. By the way, it was hard not to burst out laughing at Jerzy Pilch’s precision (like I mentioned a few posts ago).

On the other hand, if there is an example of a composer who strived to follow strategies and plans in building expectations, living up to them, or sometimes delaying meeting them, it could be Lutosławski. I’d say his music is excellent not thanks to but rather in spite of those strategies...

Conversation, alike progression, goes in many different directions. There’s the eternal melodrama of grudges and misunderstandings.

I’m sailing on. The wind is favourable. I can already sense and almost see that the land, the harbour, the destination. As if I had already sailed into the bay, which offers both shelter from the open sea’s waves and some peace of mind. I don't have to furl the sail yet. Everything is set so that I don’t really have to steer, either. I can't go below the deck and fall asleep, but up here, outside, it’s pretty nice, too.

(transl. Zuzanna Wnuk)