2. Part One

The first part is finished.

The result is a slightly more than 20-minute long arch -shaped form with two climaxes (so, archery-wise, it resembles an Eastern recurve bow).

The beginning of composing a dramatic form, at least in my experience, is always about seeking shapes which could be relevant or significant to the libretto. I don’t think of it in terms of “leitmotifs”, though there is certainly some analogy here, but rather as free-form symbolism that guides the choice of sounds: consonances, sound and rhythm sequences, and ultimately, the form.

The thematic threads of the libretto and the characters are the starting point. I read the lyrics, get familiar with the characters, and start to care about their fate. It’s not yet comprehension but rather observation and empathy. I’d say my mind wanders through the libretto until it starts to bear meaning and sound, and the sounds correlate with the lyrics.

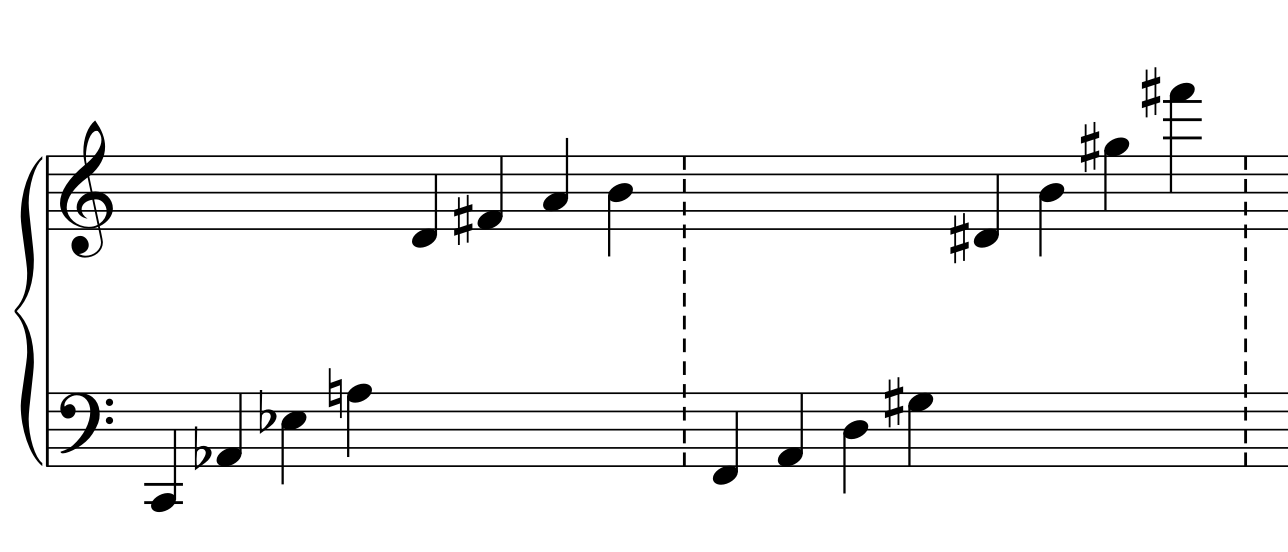

This correlation may work in two ways: in the abstract-numerical way and the impressionistic-moody way, let’s say. In the former, the focus is on what matters solely to musicologists and theoreticians; that is, various properties of sound structures such as proportions, symmetry, buildable scales and sequences, potential operations such as inversions, transpositions, decelerations, accelerations, and so on, and so forth. At times, an aspect belonging to this actually extremely boring realm starts to appear equal to the task to me. Why, it’s hard to say. Sometimes it stems from reasoning such as, for instance: consonance means stability, dissonance – volatility. Or, sometimes, there is no rational explanation; I just know that, let’s say, Ninszubur from Ahat-ili is an f-fis minor second interval – and around it, there will be a twelve-tone that I associate with the fate, and I can’t help it.

In the second type of correlation, sounds are related to mood-like feelings. I mean the kind of feeling when you associate the music you hear with a strong impression stored in your memory. For instance, the music you were listening to while reading a book, or the soundtrack of a good movie, or a carol, or a childhood lullaby. In this case, the mood does not stem from the past, but rather from the lyrics. The way the characters could be feeling in a given moment, or the mood a given fragment of the text evokes in me, develops into particular sounds. Melodies, harmonies; sometimes, rhythms. At the beginning, they’re not very defined, fragmentary. Over time, they grow clearer, yet they never take a complete shape before I get to grips with the score. Only after an attempt to write it down am I able to hear it better. When written down, in turn, it starts to live a life of its own. It sprouts. Or, perhaps better still, the process of cell division begins to take place.

Anyway, at this stage I need to get down to composing the proper score, which to a great extent will already be the final version. When I know the libretto well, thinking about it quickly becomes fruitless. Having at my disposal only snippets of varying size, I need to stitch them together, though with no clear design to follow. Interestingly, though the final shape depends, to a vast extent, on me, I normally can’t help feeling that I’m discovering this shape rather than creating it. That the design already exists somewhere beyond my consciousness, or even that the consciousness is of more harm than it is of help. It is a process somewhat similar to recalling a dream. Dreams can be more or less clear and elaborate, yet they always seem to have two layers: the first one is about people and events, and the second one, about emotions – sometimes very vivid ones. All of it fades away quite quickly; first, we forget wat we felt, and the memory of what happened is also becoming blurry. Only active effort allows to pertain at least a shade of the memory. Similarly, reading the libretto generates some kind of vibrations, which fade away unless written down, according to the thermodynamics law, which seems to work here, as well.

So, these are the lyrics of the first part of SIREN, which, with the author’s consent, I publish in two versions – the original and the final one – in case someone is interested in their comparison:

Syrena cz. 1 - wersja pierwotna

Syrena cz. 2 - wersja ostateczna

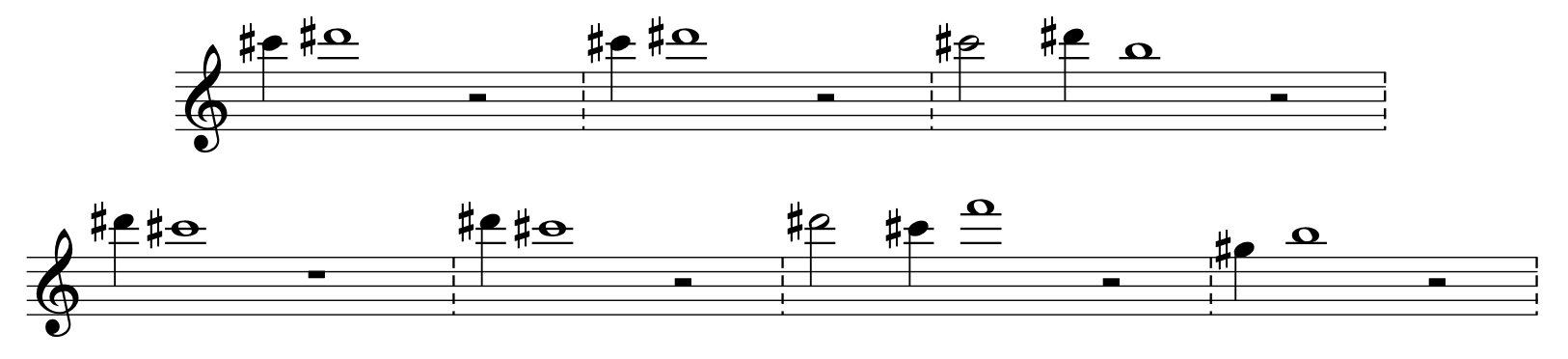

The core of the material that makes the first part involves thinking about the sea and the Siren. To some extent, they are one and the same character, as, indeed, Szczepan suggests. The sea is a vast, ambiguous, all-embracing potential. It is possible to see in it your reflection that calls you. It is an unclear calling, tempting to listen carefully. Seemingly soothing. Terrifying. The Siren’s song is such a calling, and her body is a reflection inviting a closer look. Having established that, I started to ponder the human vocal scale as a clue of sorts. As a matter of fact, the scale is not too far-reaching. The human ear is able to hear a much wider range of sounds than the human voice is able to produce. It sprang to my mind that all that’s related to the Sea/Siren should encompass the thresholds of the register, both still within and already outside the vocal scale. Humans recognize themselves in it, yet they also see openness to the borderless horizon, beyond themselves. The first theme revolves around the upper threshold register of the highest voice, and it is built in a reversible way. It could be named the theme of the Siren’s song:

The last two notes return to a register accessible to most sopranos, and they lead to another theme –the sea theme, let’s say. There are some waves here; there is also reversibility:

When compared, these two themes reveal two symmetry axes: d (which makes the former theme symmetrical) and gis (analogous for the second theme). They form important points in the material that I use in this parts, and that I will probably keep using in the following parts, as I typically can’t resist such consistence. Actually, these two sounds are also noticeable symmetry axes in a piano keyboard, which seems not to matter too much, but was an additional argument for the distinction of those sounds. This forms the basis for the Siren’s entire first line – the one about her song.

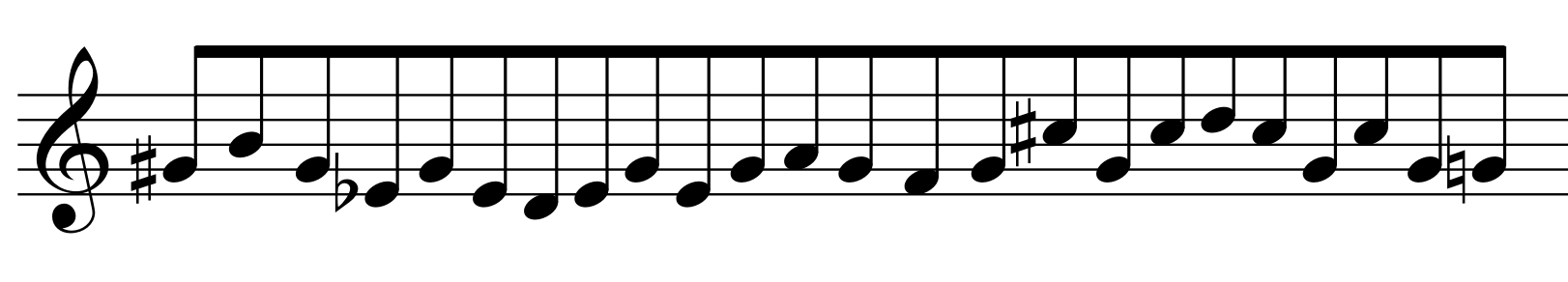

Next, there is another figure built of sequences of intervals, which decrease from a minor sixth to a major second, starting from c; and then increasing from a major third to a minor seventh, starting from f. This is still the sea with its continuous reversibility, though less obvious in this case; here, I feel its power and horror rather than tranquility. So, accordingly, this is the background for the Man’s song about fear.

By the way, fear is what I remember best from my maritime adventures. I’m not sure if everyone experiences it in a similar way; perhaps I am just exceptionally fearful. Either way, while sailing, I actually felt fear all the time. Continuous fear similar to pain; fear of or for nothing in particular. Fear intensifying as the state of the sea changed. Sometimes petrifying. To my mind, it is a fear that appears before absolute chaos. It is an uncertainty of what might happen and how I might react to it. Fear of external chaos and the corresponding internal unpredictability. In fact, it is a sense of threat to one's deepest identity. A sense of one’s self is tied to continuity, to threads that are possible to maintain, predict and remember. In a clash with chaos, the threads disintegrate. There is more to it than just an animal fear of death. It is a fear of emptiness.

The Man experiences this kind of fear. Majestic at first, it grows violent. At the beginning, his consciousness and identity are only starting to emerge and develop; therefore, his fear is also only arising. It bears more resemblance to astonishment than to horror. Then, gradually, as his identity grows firm, his fear intensifies. The Siren no longer sings; she howls.

When I was first reading the libretto, I of course imagined the howl as a tremendous, rumbling gale. Then, however, I recalled moments from the journey across the North Atlantic to Iceland, through what was essentially a constant storm. Objectively speaking, I don’t think it was a deadly threat. The weather conditions were rather typical of early spring in that area; under those same conditions fishermen keep fishing and container ships glide smoothly to their destinations. Yet my world was collapsing. Not collapsing in a spectacular, vehement manner, though; it was rather fading away. The noise of the world seemed to reach me in short bursts; between them, my mind was filled with silence. Therefore, it is the same here.

After that, there is a breakthrough. The Man rises and straightens up. Perhaps the boy he used to be becomes a young man. He is growing stronger and gaining momentum. Again, there is a wave motion with a disrupted symmetry in a third; in a theme that was already playing in my mind during one of the cruises, and I have already used it once, in “Wyspa wichrów i mgieł” (English: “Island of gale and mist”):

The man is not yet aware of the destination and the purpose, but he keeps swimming. The sea calms down. With a progression based on that theme, it returns to the former figure of “horror”. Yet this time the Man is not singing about fear but rather about the emerging question of what is best for a human being, following the story of Midas chasing Silenius, quoted in Nietzsche’s “The Birth of Tragedy”, as Szczepan told me. This thread is yet to return.

I have an idea for the interlude, somehow associated with the current situation. For now, however, I will keep it a secret. Tomorrow I will be working on the dialog between the Siren and the Woman.

(transl. Zuzanna Wnuk)